Eugene Matusov, University of Delaware, ematusov@udel.edu

AERA

2000, Symposium "Critical dialoguing"

This symposium examines ways in which university students and instructors learn through their engagement with one another in the context of an educational experience that links university coursework to a field placement working with youth in an after-school program located in a Chicano/Mexicano community agency called Barrios Unidos (BU) (Santa Cruz, CA) during 1996-1999. Courses are organized to involve undergraduates in designing a safe learning environment for the children and themselves and in reflecting on and analyzing their experiences with children in the BU/UCSC-Links After School Program (i.e., practicum). Students are expected to examine and critique the existing classroom and practicum practices (utilizing various resources, such as their personal experiences, discussions with community members, and literature), to raise concerns and issues, to provide suggestions about how to make changes and address concerns, and to participate in decision making about program practices. We have developed the term “critical dialogue in action” to describe a way the students and we (i.e., university instructors) participate in our project when we jointly consider our work with children, particularly as it relates to an emerging issue or dilemma. Presenters utilize a variety of data sources including students’ contributions to internet web discussions, student interviews, and their own observations of events that transpired in class and at the after school site. Drawing on these qualitative methodologies, each presenter contributes to an understanding of what comprises critical dialoguing in action and the transformations to which it contributes via case study descriptions of key transformative events involving the students, instructors, and children.

In our work with children and undergraduates, we have been guided by an approach that conceives of learning as a transformation of participation recognized and valued by learners’ communities (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Matusov, 1999; Rogoff, 1990) . Learners’ involvement in these activities is supported and transformed as they collaborate with other community members so that all participants in a given activity play an active role in the learning process. As they participate in shared endeavors of cultural significance with others, learners take on new roles and relationships. Pedagogical perspectives that draw upon this view of learning emphasize the following: collaboration or shared involvement in activity; involvement in activities that are meaningful and of interest to participants (i.e., shared ownership); and choice, particularly as it relates to the nature of the activity participants pursue and the form of their involvement.

In an effort to better characterize the nature of our transformation in participation, we have developed the term “critical dialogue in action” to describe a way students and we participate in our project. As we see it, these dialogues have become venues of engagement during which we share, draw upon, refine, and reconceputalize our varying perspectives and experiences, especially as they relate to an issue or dilemma. They often entail a negotiation of project goals and participants’ values. Unlike conventional notions of dialogue that conceive of it as a verbal process, critical dialogue in action is a process of negotiation that transcends forms of only linguistic expression. Throughout this negotiation, participants work together as partners, engaged in dialogic turns that are accomplished via actions and reflections, including forms of linguistic expression. Hence, the roles and relationships of participants engaged in critical dialoguing contrast markedly with notions of teaching and learning that conceive of participants as individuals who implement or receive a prescribed curriculum or set of instructional practices and participate in mostly dyadic hierarchical forms of interactions.

The goals of critical dialoging are not the discovery of a “right” answer or just finding a resolution to a problem. Instead, they involve primarily processes of transforming ownership-based engagement as we jointly consider and do our work. When resolutions do emerge they are often temporary and yield a chain of problems and considerations that beg our further reflection and action. Hence, the dialogic process we aim to describe here is characterized by a spiraling and spinning trajectory rather than a linear from here to there, process to product, means to ends pathway. As we spiral and spin, we loop forward yet backward in circular motions so that we reconsider a past concern from a different vantage point, thereby rendering a multifaceted and unpredictable spin on the way our participation in the project transforms. We consider the progress in our practice by comparing new and old problems, by pondering consequences of our actions for us and other people, and by reevaluating our priorities -- in other words, our new ways of being. We hope that this new concept will help educators and researchers involved in designing and analyzing innovative educational programs based on a “community of learners” framework.

This case study, focused on one student named Henry, analyzes transformations of the student’s participation in working with the BU children during the first UC links course (Fall 1996). In our analysis of the case, we argue that his transformation was promoted by the instructors’ collaboration with the student even when they disagreed with his educational approach. The events described here are, in part, triggered by Henry’s firm belief that testing was a necessary prerequisite for teaching and learning. He thought that testing was the only way to learn about the educational ability of children necessary for determining an appropriate instructional level.

Having many students in the project, who actively subscribed to an adult-run educational philosophy, posed an interesting dilemma for us as we tried to promote a collaborative educational philosophy based on mutuality and shared responsibility for providing guidance and managing learning. Teaching is always a goal-directed activity but we struggled to define what was our teaching goal. Did we want to make all our students think like us or should we leave alone them with their own beliefs? Our dilemma was that, on the one hand, we could not get along with the students pushing for creating an adult-run learning environment at the BU – we did not believe in an adult-run guidance, could not do it well, and tried to find alternative, collaborative ways of organizing learning environment. Moreover, it was obvious that many of the BU children had been failing in an adult-run environment in their schools already – it would not make sense for us to repeat the same educational failure at the BU. Finally, what about the other students who wanted to try other educational philosophies – how to address their needs in guidance how to guide? On the other hand, we were aware that overruling and dismissing the students’ concerns and requests for guidance within their adult-run teaching approach would be by itself our reconstruction of an adult-run approach so undesired by us. We did not want to impose or transmit our collaborative educational model to the students who do not see a need for it. We were stuck.

We discovered a direction for a possible solution of this dilemma in the following events occurring in the first UCSC-BU link class that Eugene (as the class instructor) and Pablo (as one of two TAs) taught. Once, there was an intense classroom discussion about how to run program better. The class was split almost equally into two groups (with fuzzy boundaries) expressing two major different approaches. The first group of the students insisted that we had to test all BU kids in reading, writing, and math in order to diagnose and prescribe individualized sensitive guidance for the children. They criticized kids playing games in the program as not having much educational value. The other group of students disagreed that the games did not have educational values and cited many examples of children’s learning reading, math, writing, and much more in the games. The second group did not want to get along with the idea of testing and “lecturing” (or “quizzing”) the children because it would be repetition of the same type of guidance that failed the kids in the first place (namely in schools). These examples of children’s learning in games apparently did not satisfy the first group because they rejected “occidental” learning and instead argued for establishment a comprehensive learning system.

Eugene, Pablo, and the other TA suspected that these two groups simply had different educational philosophies. They really liked the class discussion because it demonstrated students’ ownership for the program and focused on philosophical issues of guidance. However, they did not know what to do. On the one hand, they wanted to side themselves with the second group because they did agree that the children learned a lot from the games and the students assisting them in the games. They also saw this learning as authentic because it was embedded in the activities that the kids owned. These game activities, unlike activities in schools, made the children competent, active, successful, and willing learners. However, on the other hand, the instructor and TAs suspected they could not convince the first group of students by arguments. There was also a great danger of silencing (or perception of silencing) if the instructor and the TAs openly joined the second group. The instructor and the TAs also suspected that one of the reasons that words and descriptions of examples of kids’ great learning from the games did not work for the first group of students because these students did not know how to deeply engage with BU kids playing games and provide guidance within that engagement. So, the instructor and the TAs made a decision to prioritize students’ ownership for the program over their disagreement with the first group. They suggested the students from the first group start testing the kids as they saw it necessary with the purpose of reporting about the results and their experiences in the class. They also asked the second group to bring more examples about kids’ learning reading, writing, and math while playing games. Eugene and the TAs wanted the first group to experience and reflect on the consequences of testing and compare their relations with the kids emerging in testing with the relations of the other students with the kids emerging in playing games together. There were uncertainties and risk involved with these suggestions. The program could evolve in a community of test makers/takers, the BU kids might lose interest in the program and stop coming, and disciplinary problems perhaps along with adversarial relations might emerge.

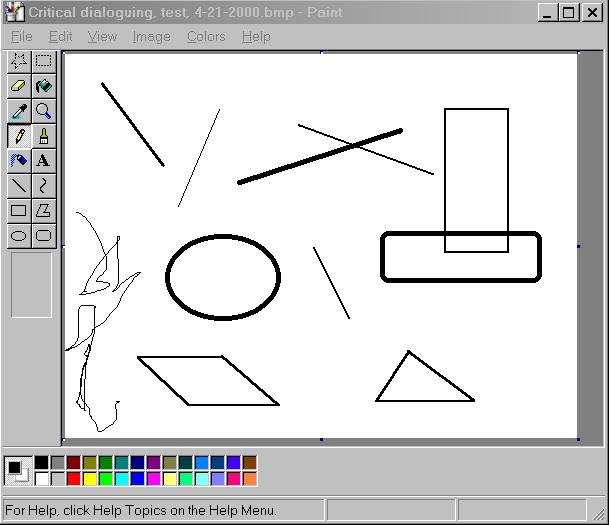

In a few days, one student from the first group, named Henry, came to Eugene and Pablo after class to ask for advice about how to test all BU kids in reading, writing, and math. After trying a test out he had developed on a few children, Henry asked instructors for advice on how to keep children on task when testing their academic skills. Henry saw the solution to the problem as tighter control of the activities at the BU and eliminating “non-educational,” “purely entertaining” games. One of his tests was on recognition of geometric figures by using the Microsoft Paint software for Windows 95. He asked children to draw and label geometric figures (e.g., triangles, circles, squares) thinking that this test would prepare children for learning the software as well as diagnose their possible educational handicaps and “behindness.”

Henry thought that, unlike traditional paper and pencil tests, these tests were authentic because there were “hand-on” and “fun.” He noticed that many BU children chose to play with the Microsoft Paint program but, thought, the program was too difficult for them. He wanted the instructors to limit BU activities to only “educational” ones so that the children would learn academic skills and not be distracted from his tests.

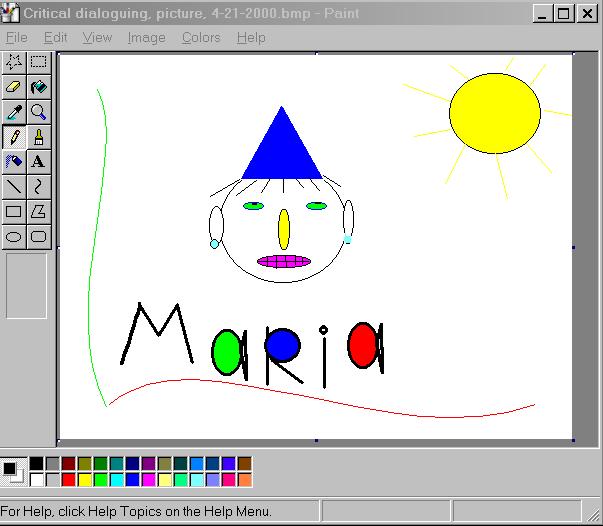

In the discussion with Henry, Eugene and Pablo tried to focus on revealing Henry’s tacit assumptions about learning. They asked Henry why he needed testing if he could see how well the kids could work with geometric figures while drawing on the computer. Henry insisted that testing was always the prerequisite of sensitive guidance. Their conversation then shifted to a discussion of Microsoft Paint (i.e., what kind activities can be done with BU kids using this software). Sitting at the computer and playing with the program, Eugene, Pablo, and Henry concluded that Microsoft Paint was not a very good program for drawing, but very useful for making collage pictures using preexisting geometric forms available in the program. Eugene suggested that Henry develop several attractive pictures (e.g., faces, houses) using the geometric forms available in Microsoft Paint, show the pictures to the kids, and help the kids to create their own the collages. Henry was a bit skeptical about how creating collages with kids would help him to diagnose “where the kids are in math.” Eugene suggested that Henry try and compare both approaches. Both Eugene and Pablo asked Henry to report about his experimentation with activities and testing in class.

Henry resonated to this advice thinking that a more attractive activity would keep children on task. The instructors’ suggestion that Henry and the children make collages with Microsoft Paint was an occasion of so-called “boundary object” (Star & Griesemer, 1989) , meaning a coordination of participants’ different perceptions on and uses of the same object. Boundary objects force participants to coordinate their diverse perceptions, functions, and roles in the activity.

After making collages with children, Henry told instructors that he was very excited because the kids liked the activity, learned a lot, and, for the first time, enthusiastically asked him for guidance. He also acknowledged that he was very surprised to find that testing was not necessarily a prerequisite for sensitive guidance. He noticed that he “almost did not think about guidance” -- the activity itself and the kids guided him how to guide them. Later in class, Henry shared this experience and told his classmates that he was confused about his role with the children and unsure about the approach to teaching that he advocated. Some students, who, like Henry advocated adult-run approaches to teaching and learning, also revealed that they had problems engaging with kids. In contrast, students moving toward a more collaborative approach to teaching and learning provided alternative approaches and examples of how to engage with the BU kids while playing games. As Henry and other class members struggled with the issues of their role at BU and how to engage with the children at site, they found themselves in a community of people who seek collaborative guidance and struggle with their own transmission-oriented educational backgrounds.

Neither Eugene nor Pablo expected the change in Henry (as with many other students later on). What they had wanted was to help Henry experience collaboration with the kids and compare it with his previous experience testing the kids. They simply had wanted Henry to enjoy working with the kids rather than diagnosing kids’ educational handicaps, or fixing kids to make them fit some imaginary “norm,” or struggling with kids to keep them on task. It seems to us that Eugene and Pablo took Henry’s concern about kids not doing his tests seriously and tried to address it from their own perspectives. They believed that the solution to Henry’s problems lay in improving the quality of his activity so it would become meaningful for the children because they own the activity and participate in defining the goal of the activity. When Henry had tested the children, the goal of the activity was not open and negotiable for them. We doubt that this transformation in Henry’s participation with the children would have been possible if Eugene and Pablo had told Henry that the problem of kids not wanting to engage with his tests was in his own adult-run teaching approach. Thus, at their meeting, Eugene, Pablo, and Henry had created a zone of a shared problem. Although they had different visions of how to approach to the problem, they all recognized that the problem and Henry’s concerns were serious and real.

In our view, Henry’s transformations occurred because a process of goal negotiation in the project became open for all participants and not because Eugene and Pablo were right and Henry was wrong. This collaborative approach to providing guidance does not require a common (shared) vision or a common (shared) educational philosophy on the part of the instructors and the students (Fullan, 1993) . For a problem to be shared, it does not need to be perceived in the same way by all the participants. Rather, all participants should recognize and acknowledge the concern that generates the problem as genuine and serious. In this case, Henry had been dissatisfied with his engagement with the kids and Eugene and Pablo, who had seen serious problems in how Henry worked with the BU kids, worried that Henry and the children might develop adversarial relations. All three were concerned about Henry’s engagement with the children. However, it was clear that Henry saw the problem in the BU “distractive” environment, while Eugene and Pablo saw the problem in Henry’s efforts to monopolize and control the activity.

Fullan, M. (1993). Change forces: Probing the depth of educational reform. London ; New York: Falmer Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge England ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Matusov, E. (1999). How does a community of learners maintain itself? Ecology of an innovative school. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 30(2), 161-186.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York: Oxford University Press.

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, 'translations,' and coherence: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley's museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-1939. Social Studies of Science, 19, 387-420.![]()