By

Jan Sajko, art teacher of Jarovnice Elementary/Middle School#1, Slovakia

![]()

Jan Sajko has become widely known because of

his extraordinary success in awaking the artistic talent of his primary school

students in a very poor Romany settlement in eastern Slovakia. Sajko is employed

as an art teacher in the all-Roma public school in Jarovnice, the largest Romany

settlement in Slovakia. The settlement, located on either side of a quiet

stream, hit the headlines in 1998 when the stream flooded, killing 50 residents.

The paintings and drawing of Sajko’s students have been shown in numerous

exhibits around the world, and have won many awards.

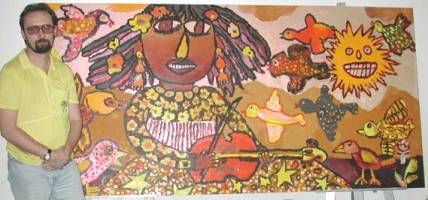

My

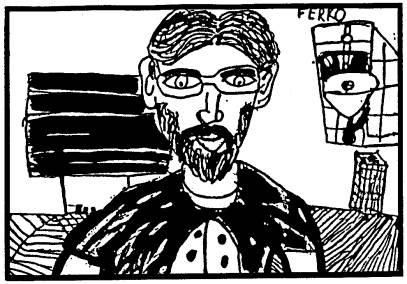

Teacher (Jan Sajko) by Milan Ferko (14-year old)

In this report Sajko explains that trying to

use standard Slovak teaching methods with students from poor Romany communities

often fails, leaving the children feeling incompetent and uninterested in school

work. Such children, he says, need more individual attention than do those from

more middle-class Slovak homes. In his art classes, children are encouraged to

work at their own pace, and to find pleasure in their creative work. The

teacher’s aim must to be to work with the children from their starting place,

use their experiences and points of reference as themes, e.g., “my family,”

“experiences I have had...” There

is great scope for drawing on the richness of Romany culture. In helping

students find artistic themes, Sajko teaches lessons on Romany history,

traditional crafts, and musical instruments. He invites students to illustrate

Romany songs and folk tales. Sometimes the children provide songs or tales and

translate them into Slovak so the class can discuss ideas for illustrations.

Students are encouraged to find their own personal ways of expression; classes

are taken to visit art exhibitions. The hardest working and most creative

students are rewarded by going on trip abroad with Sajko to exhibitions of their

work. The aim is always to teach

students that through hard work they can change their lives; they are not

condemned to the life of poverty and idleness that they see around them.

Additional description of the life in Jarovnice and Mr. Sajko work can be found on the webpage: https://angelfire.com/on3/jarovnice made by Pawel Bakowski. A description of the recent exhibit of artwork by Sajko’s students, in Heidelberg, Germany can be found on the webpage https://www.mitost.de/Berichte/Roma99/roma-galerie.htm

1976

graduated from Artistic High School in Košice, Slovakia

1977-1978 designer, photographer for the shoe factory JAS in Bardejov

1978-1982 student at Pavol Šafarik University, Dept. of Education

1982-1983 artist, designer, Sabinov Cultural Center

1983-1986 art teacher, Elementary/Middle School in Brezovica

1986-2000 art teacher, Elementary/Middle School in Jarovnice

![]()

I met first with Jan Sajko indirectly, through

a story of my friend Pawel Bakowski whom I invited as a guest speaker to my

class on multiculturalism and education. Pawel made a PowerPoint presentation

about a phenomenal art teacher from Slovakia who works with Roma children. At

the end of Pawel’s presentation, many of my students cried and I tried to keep

myself from crying. Next class meeting after the presentation, my students asked

me how to become a teacher like Jan Sajko. I thought, “I wish I could talk

with him…” Fortunately, again thanks to Pawel Bakowski’s and his

family’s efforts, Jan Sajko came to US and we had many important conversations

about his pedagogy, which are reflected in this article.

When asked why he started working with Roma children, Jan said that may be it was a matter of chance or may be a matter of fate. When Jan was a young boy he was mugged and severely bitten by a group of Roma teen boys unknown so he had to go to a hospital. Jan's father asked him, "How can you teach Roma children, don't you forget how they beat you?!" Jan laughed, "Maybe because of this experience I became a teacher of Roma kids..."

Jan

insisted on not using the word "gypsy" to describe Roma people. In Europe

the word "gypsy" is derogatory -- it means "to beg" or

"to steal." It is impossible to separate Jan’s pedagogy

from his participation in art; cultures; Roma folklore, music, and history;

politics; innovative schooling; politics; and humanism. Using modern technology,

we tried to combine these aspects together in this presentation.

This article was based on Jan Sajko’s journal paper published in Romano Džaniben, 3-4/1999, pp.31-40. I asked him to elaborate and provide examples of his ideas expressed in the journal article. I think that this article will be interesting for all educators in the US. Jan’s presentation at the School of Education, University of Delaware, on 7/14/2000 attracted a lot of interest from US scholars and educators. His two-week extremely successful work with ethnically diverse children in the Boys & Girls Club of Wilmington, DE (see below) proves that his instructional method and approach can be applied to diverse conditions and institutions. Without doubts, Jan Sajko is one of greatest educators of our time. This is Jan’s first publication of his teaching approach in English.

I want to thank Jan Sajko for

his time he spent with me; Pawel and Ella Bakowski for organizing Jan's visit,

paying many expenses, and for introducing him to me; Janell Binder for helping

Jan in organizing his visit in the US; Renee Hayes for editing this website;

School of Education at the University of Delaware for sponsoring Jan's

presentation; Liz Pemberton for helping in organizing exhibition; and many other

kind people who helped.

Eugene Matusov

Assistant Professor of Education, University of Delaware, Newark, 8/7/2000

|

Ján

Sajko, Art Teacher |

Eugene

Matusov |

![]()

Elementary and middle school in

Jarovnice (near Prešov town, Slovakia) is attended only by Roma students (682

students in 1999/2000) who are mostly living in very poor social conditions in a

Roma settlement. It is on the edge of Jarovnice village divided from Slovak

residents. It is a real modern day ghetto of our days.

|

|

|

The inhabitants, forced by

Communists in the 1950s to abandon their nomadic lifestyle, settled there and

built this village with their own skills and with almost no assistance from the

government. There is no sewage system in the village, malnutrition and sickness

plague the people, and with unemployment reaching 100%, virtually the entire

population is on welfare. None of the elementary school graduates continue their

education, and almost nobody gets a job after graduation.

|

|

|

A majority of Roma children came to the school not prepared to go to the first class. They do not have the hygienic and cultural habits expected by a traditional school. This requires from the teachers more pedagogical efforts and a more individual approach than would be required for teaching mainstream Slovak middle-class children. Each teacher, if he or she wants to be successful in working with these children, has to ground his or her work in the children’s reality. The targeted academic curricula have to be adjusted to the children’s reality in a way to start where the children are and then to progress to the desired goal at a pace that is comfortable for the children. A traditional instruction and pedagogical practice, which is developed from and aimed at mainstream middle-class Slovak children and community, does not make sense for those Roma children. Children from socially and economically disadvantaged conditions cannot match the instruction, curricula, and pace of a traditional school. For example, I noticed that the hand muscles of many Roma first grade children are not developed enough in comparison with mainstream middle-class Slovak children so it takes more time for them to learn how write and draw. In addition to that, the Roma first graders have to process a lot of information in the Slovak language, which is not their native language. If we used a traditional instruction, Roma students would fail academically, become academically handicapped, and lose self-confidence and motivation for academic school learning, which often leads to a negative attitude toward an academic subject and toward school in general.

![]()

|

|

Aesthetically cultivate the whole person of a student who comes to school from a socially and economically disadvantaged living conditions; |

|

|

Deliberately work with the student’s thinking, feelings, and actions in order to transform the student’s value system; |

|

|

Respect the individuality of the students and their diverse psychological, intellectual, emotional, and physiological development; |

|

|

Develop a disposition to an artistic creativity in Roma students, lead them to spontaneous work in art, and promote a strong and positive self-identity (“romipen” in the Roma language meaning of proud to be a Roma); |

Roma Carriage, team work, 1992, the design by Marek Červeňák

![]()

1. Forget about time pressure (i.e., do not expect that students’ work will start and finish at one lesson);

2. The highest teaching priority must be the students’ activities, their joy from the work and from the result of that work (not time, not covering the prescribed curricula). The teacher must work for the students not for fulfilling bureaucratic requirements;

3. Each individual student works and learns at his/her own pace;

4. Students should have choices for their art techniques and projects in the class activities at any time (besides giving the students freedom to develop their own choices, the teacher has to be ready to offer at least two-three alternatives of what and how to do art projects in the classroom). An art lesson should not be like army training when soldiers do exactly what the commander tells them to do – students’ own free choice always must be a part of the lesson;

5.

The teacher must make students’ classroom work meaningful, practical,

and socially visible. For example, the teacher should use all opportunities to

decorate and beautify the school’s interior with the students’ artwork made

in the classroom.

6. Students’ teamwork should be encouraged, offered, and organized.

Several children work on the same picture

Teamwork helps to resolve many problems at school. For example, when we started hanging individual artwork on the school walls, some paintings got vandalized. To fight that, I brought a big sheet of paper that I carried from class to class. It was so big that the children had to paint together. It was one of the first paintings hung on the school wall that was not vandalized because all children of the school took pride in it. Now thanks to in- and between-class teamwork, we do not have this problem of vandalism in the school.

7.

It is very important for the teacher to create a positive and inviting

atmosphere for his/her lessons. This means that the teacher must find sensitive

ways of communication with each child;

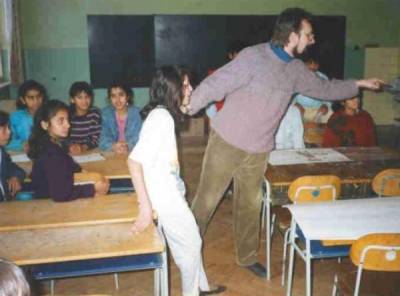

Photo courtesy of Marcia Barbacki

I introduce my students into the fairy-tale realm of the old Roma legends and teach them how to express their feelings and how to present their ideas in the form of art through painting, drawing, and sculpture.

![]()

The basic teaching principle is to gradually move a student from the concrete to the abstract. This means that the student moves from familiar, known, and understandable to unfamiliar, unknown, and initially incomprehensible. I often start my teaching with new students with playful drawing humans (e.g., a portrait, a human figure, a composition of human figures).

For example, on my first lesson I often teach

children how to draw the human face. On the first lesson, I do not give my

students pencils and papers. Instead, I use my communication with them, chalk,

and the blackboard. At the beginning, I ask the children if they have siblings

who are or were my students, whether they like to draw, what they like to draw.

My goal is to develop a positive attitude to art by drawing on positive

associations the children have encountered in their lives. Then I often talk

about how to draw my face, saying that it looks like a cucumber (children often

laugh at that). I ask the students to compare their faces with mine and tell

what different shapes they have (e.g., circle-like, corner-like). Children

really like this activity. After that, I ask children to help me to draw a human

head via a series of questions like what a head has. I draw exactly what they

say but place it in different parts of the face on the classroom blackboard

(e.g., I put the nose on the bottom of the face, both ears on the same side).

Playing with how to draw a human head (examples). Children give me instructions to draw: 1 head, 1 neck, 1 nose, 2 ears, hair, 1 mouth. I try to draw what the children said on the blackboard but I intentionally misplace the parts of a human face and distort the face proportions in order to attract the children’s attention to the appropriate positions and proportions of the parts of human face (and body). The global goal of the activity is to encourage the children to draw so they won’t be afraid of paper. I prepare them to meet the artistic reality – it is a game and funny. It is a joy to draw!

The children laugh at my drawing but they start noticing

that it is very important where they draw each part of human face and what

relative size it should be. To facilitate their reflection, I ask them why they

are laughing, what mistakes I made, how to fix them, and what is important in

drawing this face correctly. By doing that, I invoke students’ understanding

of human proportions and develop a new motivation in students to become

sensitive to place and proportions. It is very important that the teacher

accepts students’ understandings and ideas to promote their own artistic

thinking rather than to transmit information about art that can be indifferent

to the individual children. By accepting students’ ideas, I do not mean

“everything can go” because children can see immediate outcomes of their

ideas as I draw what they say on the blackboard so they can visualize their own

mistakes and correct them. The information about art and artistic techniques

emerge in the classroom interaction between the teacher and the students and

among the students. Students are free to speak in my class (no special rules of

taking dialogic turns like raising hands) unless, of course, several children

try to speak at once – in this case, I manage the discussion.

The teacher promotes an artistic vision in all children.

Children start looking at themselves and each other, measuring, comparing, and

calculating proportions of different parts of the human face and body. In

collaboration with the teacher, the students build the results of these

measurements into their artwork. For these beginning art activities, it is

helpful to use the class blackboard. For example, I often prepare a

mini-competition among three groups of the students on the best picture, decided

by the whole class. I split the class into three groups (often by rows where the

students sit). Each group consists of 2-3 active artists working on the

blackboard (divided into three equal parts) and the rest of each group provides

advice, guidance, and feedback. The 2-3 artists representing the group are the

choice of the group. At the end of the competition, each group gets applause and

the whole class votes on the best picture. I can’t emphasize more that the key

for teaching success is the teacher’s communication with the students and the

playfulness of classroom activities. Using the classroom blackboard for

communicating ideas about art techniques helps the children to stop being afraid

of blank paper. After these lessons on the blackboard, my students become ready

to start drawing on paper. I introduce simple techniques using pencil and paper

first and then, gradually, move to an introduction of more complicated

techniques of painting, such as working with ink, watercolor, tempera, and

collage. At the beginning, they draw everything very small at the bottom of

their sheet for paper, but then they gradually become more adventurous in

experimenting with positioning figures on the entire sheet of paper. They start

filling the blank space of the paper and mastering it with ease. Their drawing

becomes more joyful for them.

![]()

|

|

I suggest students themes for artistic work that are familiar, meaningful, and important for the students such as “my family” and “important events and experiences for me.” These themes can help to develop better relationships with other people, better attitude toward the students’ artistic work, and respect for the students’ own work. |

Jozef Červeňák, 14-year old, works on the picture Marriage, 1999

|

|

At the root of these themes of the students’ artwork are problems in the students’ lives that they often do not know how to resolve by themselves. |

|

|

When we work on these art themes, I try to integrate other fields of culture such as the history of Roma people, important historic persons (e.g., the famous Roma musicians like Cinka Panna, Ján Bihary, Jozef Piťo, Frnatišek Horváth; Roma artisans), Roma and other people’s folklore, fairytales, real live stories, songs, dances, and so forth. |

Cinka Panna,

teamwork (12-14), 1995

(to read about the famous Roma musician Cinka Panna

click on here)

|

|

Roma

traditional songs and folklore fairytales have a special place among art

themes that I introduce to my students. We read fairytales together. We hear

Roma songs either from tapes or from students’ singing in the classroom.

Since I’m a Slovak, I ask my students to translate a song into my

language. After children translate the song, we often start a discussion of

what is possible to draw from this song, so we try to make another type

translation - from the song or fairytale to picture. I place tremendous

value on these translations among different art forms (e.g., stories, songs,

pictures, Roma language, Slovak language). |

|

Čhajori romaňi (Roma lyrics) |

|

|

Roma

girl, |

Roma girl (click here to hear the song, requires MS Window Media Player)

|

|

With the help of Roma folklore, I want my students to return back to the old cultural traditions of Roma people. My children think of how people lived in the past and about the rich history, culture, and art their ancestors possessed . This makes them proud of who they are, motivated to continue Roma traditions in their own lives and to build positive cultural identities. |

|

|

I teach my students the basics of development of a picture: the principles of composition, perspective, background-foreground, building levels of a picture, and so forth. |

|

|

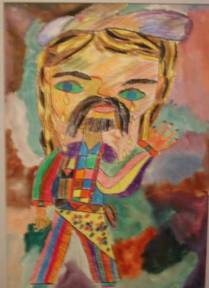

While the students work on their picture, I often talk about colors they choose (e.g., primary and complementary, cold and warm, perspective and color, color and light, using color tones in composition) – expression of feelings using colors, how to mix colors. (Unlike secondary colors, the primary colors cannot be produced through mixture of other colors.) I, as a teacher, do not try to impose my own vision of colors or my feelings in my students’ work; on the contrary, I try to support the students’ colors, feelings, and ideas they try to express in their work. I only advise them to use clear colors and help them master the art technique they chose. I treat my students as fellow artists even though I may be a more experienced artist than they are. |

The children’s freedom of using colors is very important for my pedagogy. Roma students use very special colors that I have never observed being used by children (and adults) from Central Europe. I speculate that they probably draw upon a cultural heritage from India. What is interesting and phenomenal is that Roma children from Jarovnice were not born into the Roma art culture in a sense that they were not surrounded by Roma art. Yes, they have been exposed to Roma songs, stories, dancing but not painting and drawing. It is amazing how Roma way of using colors, perspective, and composition emerge in the Roma children. They use colors from their hearts. It is Roma freedom on the paper!

Whistler, Jana Ferková (13), 2000, paper collage,

the background is made of dressmakers’ designs

from women’s journal

Horse by Ľuboš Popuša (12), 1999, pastel

It is very special and unique. The colors that

Roma children use have very powerful expressivities. It is a pure Roma soul.

Roma art enriches everybody. Looking at Roma children’s art, discrimination

and persecutions of Roma people become incomprehensible one more time. We must

stop prejudice against Roma people. It is very important for us – non-Romas.

Happy day,

Dušan Kaleja (14), 2000

In example, once I noticed that one fourteen-year old boy in my class was lying on a desk and not drawing. I came up to him and discovered that he was very tired and sleepy. I asked him what was the matter, why he looked so tired and sleepy. The boy told me that he was playing cards with his older brother and the bother’s friends all the previous night. I asked him who won the game, how much money was won, who was there, what was on the table, how would he have used the money if he had won, how did he play, what feelings did he have then and now. He was answering me with interest. Other children were also interested in the story. Finally, I asked the boy to draw how he played the cards last night. He started drawing, asking me about how to place human figures at the card table. Composition was the theme of this lesson.

Gift for baby by Jana Kalejová (12), 1997.

This picture shows the joy that the older sister (the artist) has with the delivery of her baby sister. (Note the artistic approach: the child used different size distortions of the represented figures to emphasize who is the most important in the family.)

![]()

Using these themes, the teacher can develop the students’ sense of attention to form, color, and space of an object represented in their artwork. For this development, it is important for the teacher to focus on the structure and texture of individual forms of natural and artificial, alive and non-living objects.

This art curriculum of foci on technical art problems is

better addressed in the framework of the thematic work discussed above. When

engaged in interesting themes of their choice, the students often come to the

teacher with questions of how to do it in their artwork. The teacher must wait

for this spontaneous (but promoted and supported by the teacher) interest from

the students, then the students will come to the teacher, and ask how to deal

with technical art problems. Now the students are ready for my whole class

lecture for all students. Even if some students may not yet be faced with

similar problems, they have an interest in the problem and my lecture because

they see that other students have this problem. Using this way of authentic

learning rather than imposed teaching, the students learn to resolve concrete

problems, their own problems, of composition. While working on the thematic

pictures of their interest and choice, the students learn how to create details

of nature, animals, work with décor space, clothing decorations, and so forth.

Sad song by

Žaneta Červeňáková (15), 2000,

mixed art techniques of pastels plus watercolor

When we work on an art theme portraying interiors, the students learn how to make artistic representations of artificial forms. They solve problems of representation of different objects (cylindrical, simple, regular shapes). For example, when students choose to draw a picture with themes like “our home” or “at our kitchen,” they have to deal with the problem of representation of still life which force them to ask me how to do it in their pictures.

Mother and baby

by Jana Bilá (14), 1999, pastel

Note

When Roma students in a traditional instructional setting have to work on

technical details or structure, a motivational problem emerges that they cannot

see the meaning of their work and learning; the work is meaningless and abstract

for them. If, however, the problems of décor or structure emerge from the

students’ work, then they put forth efforts and are enthusiastic in learning

how to deal with the problems. For example, a Roma student may not want to work

on a décor project that has only the teaching goal of learning how to do this décor.

However, if the student has to paint a T-shirt using a concrete character from

his picture, there is not a motivational problem for him to learn how to draw

the décor of the concrete clothing of a concrete character. He does it with

enthusiasm, perseverance, sense of purpose, and joy.

![]()

(Artwork in materials)

In sum, the teaching goal of an art teacher should be

development of artistic creativity, artistic thinking, and knowledge of the laws

of composition in all students. In our work, we often recycle disposed materials

(e.g., used paper cartons, old journals, egg shells), which force the children

to creatively stylize their artwork and to use abstract forms available in the

materials.

Note

Using these materials adds alternatives to the traditional artwork with pencils,

crayons, and brushes available in the classroom. At early grade, I start my art

classes with diverse artwork such as playing with paper forms, origami, and so

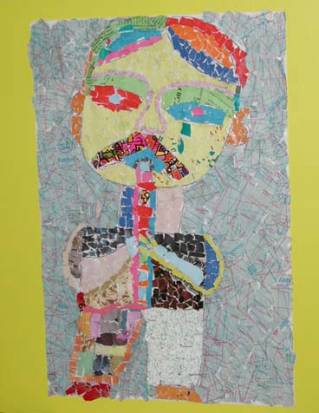

forth. For example, I have a very good experience of working with collage in a

sense that the children enjoyed doing that and produced very good artistic

results. We often use two types of collage technique: 1) tearing pages from

colorful journals into small diverse pieces, painting, and gluing them together

on the paper to make a new form and 2) cutting color paper in different

geometrical forms with scissors (e.g., circles, triangles, squares) to make a

picture from them.

Violinist

by Stanislav Bilý (14), 2000, paper collage

We use diverse art techniques in the classroom: a

combination of painting and collage techniques, different types of mosaic from

the recycled materials described above, pictures made out of white and brown

eggshells. It is possible to make pictures using fingerprints, palm-prints, and

finger painting. We also do three-dimensional pictures assembling objects (e.g.,

small boxes, used medicine containers) and papers of different thickness glued

to the paper. These types of art techniques are especially good to use in the

classroom when there are holidays and carnivals (e.g., for producing masks). It

makes students’ artwork especially meaningful for the children.

Using individual art techniques is an issue of the

availability of the recycled materials that I ask my students to collect from

the beginning of the school year. When I have an opportunity to use a graphic

printer, I try to introduce in my classes other different graphic techniques

such print from a collage, linarite, monotype, etc. Also, if I have art

materials for modeling such as clay I do reliefs and small statues with my

students.

![]()

(Art culture)

The purpose of these classroom conversations about art with

the students is to teach the students about different forms of art (e.g.,

sculpture, architecture), talk about art pieces, and express personal

impressions from particular pieces of art. To promote such discussions, I try to

visit art galleries with my students. It is very important to give the students

opportunities to experience diverse forms of art in different cultural settings.

Note

The teacher has to prepare the themes of these conversations about art

carefully, being sensitive to

individual artistic needs of the students. For example, when students are

working on an illustration of a Roma song or a Roma fairytale, it is possible to

talk with the students about book illustrations made by professional artists

(e.g., why people do illustrations in the book, how do they do it, what a

relation between the text and the pictures can be, what are different possible

approaches to and traditions of making illustrations).

It is extremely important to have an opportunity to

organize a gallery exhibition of the children’s own artwork because it has a

great deal of influence on development of the child’s feeling of

self-confidence, self-worth, and artistic pride.

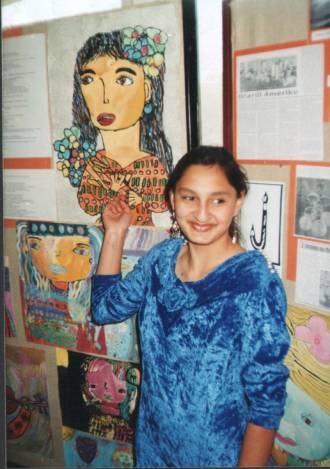

Silvia Rakašová

(14) proudly presents her artwork at the exhibition

in the Cultural Center in town Sabinov, Slovakia (April, 1997)

Students’ artwork exhibition in Heidelberg, Germany, 1999 (see https://www.mitost.de/Berichte/Roma99/roma-galerie.htm for more info about this exhibition)

It also gives the children an opportunity to find new types of role models.

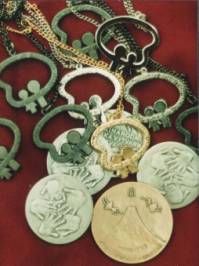

The art of Jarovnice students was recognized and awarded in

numerous national and international art competitions in India, Japan, Hungary,

Germany, Czech Republic, USA, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Norway, Finland, Slovenia,

Slovakia, and Sweden. Jarovnice artwork won competitions among many thousands of

participants. For example, in 1998, in the International Children’s Art

competition sponsored by the Nippon Television Network Cultural Society, there

were 247,293 works of art presented from around the world. Jarovnice students

were awarded two gold medals, two silver medals, and nine bronze medals.

Four fourteen-year old boys from my school went with me to the opening of an exhibition of their artwork in Vienna, Austria. In Vienna, they met with Austrian middle-class Roma people who live very different lives than do the Roma of Jarovnice. The Austrian Roma people have well-paid jobs, nice cars, clean houses and, they are very proud that they are Roma. They know Roma history well. They can play violins and sing traditional Roma songs. They are well-respected in Austrian local communities. My four students were very impressed by them, thus learning about different lives that other Roma people live. In Jarovnice, all adults are unemployed, very passive, and depressed. They are not proud to be Roma. They face discrimination from local people and Slovak authorities. Nobody goes to high school. There is a high rate of teenage pregnancy, rape, incest, crime, drug, and alcohol abuse. After coming back from Austria, three out of the four boys decided to go to high school and started preparation for high school exams. In my view, this development was a direct result of their artwork exhibition in a foreign country, other people’s interest in their artwork, and their encounter with the Austrian Roma people.

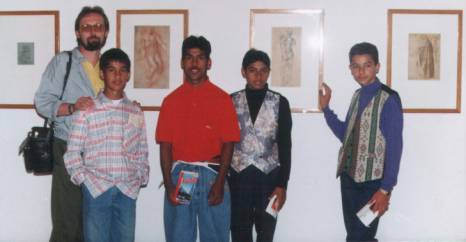

Photo of Jan Sajko

with Jarovnica Roma children (14)

in Michelangelo’s, Rafael’s, and Leonardo’s artworks

in Albertina gallery in Vienna, Austria, 1995

In another example, after visiting with the children a gallery of modern art in Stuttgart in Germany and watching an exhibition of cubist artists (e.g., Picasso), the children were very impressed by this art method, which was new for them. When they came back, they enthusiastically presented information about cubism to all children in their classroom and showed photos of cubism that they brought from the gallery. Many children from their classroom were so impressed by the presentation that they started drawing pictures in cubist style saying, “Mr. Teacher, let’s (get?) working like Picasso! We want to become Roma cubists!”

Marek

Bily, Radko Kaleja (Jarovnice students, 14), and Jan Sajko (the teacher)

in Stuttgart gallery (Germany) with Picasso’s paintings (summer, 1999)

“Roma cubism”: children’s painting

influenced by Picasso’ cubism

after Marek and Radko’s shared what they saw in Germany

with their classmates (teamwork)

The

spectators at my Roma students’ international exhibitions were very impressed

by their artwork. Unfortunately, however, we were faced with other attitudes

toward Roma artists during our trips abroad as well. For example, when my Roma

students (a few 12- and 13- year-old girls) and I were crossing Austrian

boarder, we were stopped because Austrian boarder guards suspected that I was a

pimp bringing Roma prostitutes to Vienna. A similar event occurred when I

accompanied a group of Roma boys to an exhibition in Germany. We were also faced

with an attack by “skinheads” at a train station

When people in Europe see a Roma person, often they think something negative about the person (e.g., a thief, a prostitute, a pimp, a mobster) expecting problems from him/her. It sends very negative messages to Roma children. This is a very depressing situation. I found this problem of prejudice, discrimination, and persecutions of Roma people common to many European countries. We all together should do something to stop it.

![]()

|

|

Show positive works of art by Roma students to a broad public. When there is a possibility to organize exhibits of the students’ artworks and trips to different places and museums, we must expose the children to conditions different from those in their own settlement. It has a big positive influence not only to the actual child who visits another place, but also to the entire local Roma community of Jarovnice (including adults). Jarovnice adults are positively influenced because they know that their children go to other places and bring back feelings of success and recognition from these places. |

Photo courtesy of Marcia Barbacki

A few of the

awards received by the Jarovnice Roma students

from numerous art competitions

After returning from a trip to Heidelberg (Germany) in 1999 where I was with two Roma boys on the opening of our students’ exhibition, I asked Marek Bilý (14) what was his biggest impression of the trip, what he would remember for all his life. He answered, “Mr. Teacher, it was the moment when I was staying in front of my own pictures in the gallery and all visitors applauded me! It was the nicest moment – I was very proud and happy!” The fact that students have possibilities to experience the success of their own work is very important for their development as whole persons.

To illustrate this point that the work with children influences their parents, let me tell a story. Once, our school was robbed. The thief took a tape recorder and electronic instruments that were bought using charitable contributions for Roma children which resulted from many art exhibitions of the children’s work. We had planned to use this music equipment for the coming Children’s Day celebration in our school. When we learned what happened, the principal of the school and I invited the most respectful parents from the Jarovnice community and explained to them that the thief took the equipment not from the principal or the art teacher but from their Roma children. We asked their parents for help to find and return the equipment. A few days later, in the morning, we found this stolen equipment waiting us at the school doors. It showed that there was something changed in the parents and entire Roma community of Jarovnice.

|

|

Create conditions so that the children’s heroes are not adults who bully other people, live by crime, drink alcohol, and use drugs but rather positive and inspirational characters from Roma history and present times such as famous Roma musicians, leaders, smiths, dancers, singers, writers, storytellers who despite all odds brought people joy. |

|

|

Support and encourage the most active and industrious students with new art opportunities and more exposure to diverse cultures and lives (e.g., visiting exhibits abroad), so all children know that those students who put forth their efforts and have excellent results live richer and multi-faceted lives. |

Notes

In the practice of teaching Roma children in Jarovnice, I am faced with a clear

contradiction between what my school tries to do to the Roma children and what

the rest of the society does to them. While in school, we, Jarovnice educators,

want to actualize all Roma children’s creative potentials, the society pays

their parents for their idleness and passivity using the state “welfare”

system in Slovakia. Even if a student is extremely talented and skillful, he or

she does not have a chance to get a high school education or change the

conditions of his or her life. Parents often do not support them, they do not

sign the necessary application forms for high school. Children are victims of

their parents, parents are victims of a very discriminative social and political

system and depressed economic conditions. I believe that we, citizens of

Slovakia, must change legislative processes and laws from supporting idleness of

people in poverty to promoting new workplaces demanding people’s industry,

creativity, and initiative.

Conclusion

To break the cycle of imposing idleness, helplessness, self-destruction,

handicap, and hopelessness, we must change two basic conditions:

To give people opportunity to work.

To make a big difference between welfare paycheck and salary for work encouraging people to seek employment.

![]()

What I just said above not only applies to Roma people in

Slovakia but it affects all people on the Earth. We won’t resolve “the

problem of Roma people,” we can only resolve the problem of our future (and

not only the future of one country). It is sad that we do not know how to

support the human potential that exists in many settlements like Jarovnice. We,

humankind, lose a lot potentially talented and creative people who, if there

were the possibility to work, would

make a lot of good for the whole society. If nothing changes, a conflict will

erupt. It is like a time bomb. It is impossible to rob people from their

potentials forever – they will revolt.

To avoid the waste of human lives and future conflicts, we

must create opportunities for jobs for people of all settlements and give them a

chance to earn their living by

their labor. It is easy for a state to buy itself out of a problem by giving

money to people from Roma settlements to survive (but not to live) and later to

show how Roma people are lazy, how they are drunk, how they use drugs, how they

steal, how they are irresponsible parents… Let’s look at this problem from

the other side. What chances would you have if you were born in a Roma

settlement like Jarovnice? What life achievements would you make? What

opportunities would you have to fulfill your dreams?

Photo courtesy of Marcia Barbacki

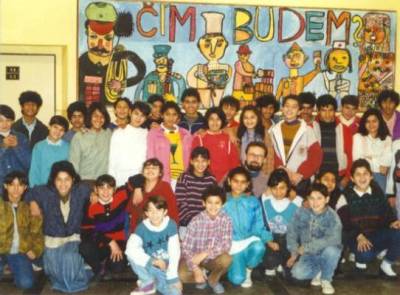

“This is the picture titled “Čim Budem” (What Are We Going To Be?). When I visited the elementary school for Roma children in Jarovnice for the first time several years ago, as an interpreter for a group of American specialists on children's rehabilitation, the school appeared to be like any other Slovakian school.

At our request, the children, smiling at the camera, lined up in front of a large painting they created in art class that represented their dream jobs: chimney sweep, soldier, cook, bricklayer, painter, nurse, singer... but none of these dreams will come true.

The village of Jarovnice, with its

population of 2500, is one of the largest Roma camps in Eastern Europe.” Pawel

Bakowski, USA, 2000.

I’m only a common teacher. I am not a politician – I do

not know how to change social situations.

We all may try to evade the problem by leaving Roma schools

and settlements and pushing them away. So what? What will change? The problems

will come as a boomerang and hit us later with bigger strength.

Many people from my country go to the third world countries

to help people in poverty there. They go to Africa, the Amazon basin, and so on.

It is very good that they go to help other people; however, it is important to

help people there. We have our own misery, our own poverty, our own despair

here, in our country. We also need helpers here. We have people who live in our

country and who need no less help than people in other countries. They may even

live in a neighborhood next to you. We should support Roma and other minority

cultures because they need to have good lives like we do and because they can

make our lives richer.

I believe that if you start work with Roma and other

minority students in school and you give them your time, your efforts, your

passion, your soul – I believe that you will meet with big thanks from the

children. And maybe even there will be a small miracle that parents may tell you

that your work makes difference in their children’s lives and say, “Thank

you very much for your work, Mr. Teacher!”

![]()

Mr.

Teacher Sajko--

We want to thank you

for leading our first steps towards paints and brushes.

You have taught us to realize that Roma people are knowledgeable about

various things, they do not only drink alcohol and stay idle at home.

If there were more people like you the Roma people would become

different...

... We hope that you will

like what we wrote during one of our literature classes. The literature teacher

asked us to write about our best friend. We wrote that we are like three

musketeers. Our swords are our paint brushes. Our weapon is paint. Our enemy is

blank paper. We have only one commander. Our commander is you, Mr. Teacher

Sajko. You are our best friend. We think that you are a very good teacher.

And we are proud that we have such a teacher.

We want to say thanks you

wholeheartedly,

Radko, Martin, Jozef, 8A

classroom, 12-19-97

![]()

Mr. Sajko, everybody likes

you in the school. Because during

the art class, as if you were a king, you take care of everybody and you

like all of us. When flowers on the

meadow grow I will give them to you.

![]()

AVER

TUT ŠAJ DEL GOĎI

AVER TUT ŠAJ DEL DROM

ALE MANUŠES TUTAR MUŠINES

TE KEREL ČA TU KORKORO

One

can give you a piece of advice,

One can show you the direction to go,

But only you must make yourself up.

(Old Roma saying)

![]()

In June-August 2000 I visited the United States, as I was

invited by the University of Delaware to give a few presentations about my

pedagogical method and experiences. During the visit, I wanted to try my method

of teaching art with American children. Thanks to my dear friend Pawel Bakowski,

I got an opportunity to work, as a volunteer art teacher, with ethnically

diverse children at Clarence Fraim Boys and Girls Club of Wilmington for two

weeks.

I worked with a group of 14 children of different ages

(from 6 to 16): 4 boys and 10 girls, 3 African Americans, 1 Latino, and the rest

of the children were white. It was very interesting for me to try to work with

such diverse children – I never worked with such a big range of children’s

ages. This forced me to talk differently depending on the child’s age: at one

moment, I had to simplify my talk with very young children and at another moment

I had to expressed a complex idea to a teenage child.

Debbie Moss (6) is

working on a paper collage,

Wilmington, DE, USA, July, 2000

I promoted the American children to work as a team on one

big-size picture as I had done with Roma children in Jarovnice. In the two

weeks, we managed to make two such pictures. One picture was made using a paper

collage technique, while the second picture was made using a finger-painting

technique. To inspire the children I used pictures and photos of my Roma

students’ artwork that I brought with me. My goal was to break their fear of

colors and blank paper, which is very common for beginning artists. I also

showed the children and read books about famous Roma people.

Jan Sajko works

with American children in the Boys and Girls Club

in Wilmington, DE

Photos by Eugene Matusov, August, 2000

They were especially impressed with old Roma clothing: full of colors, sun, and joy. I also encouraged the children to bring music to the class and we shared our music: I let them listen to Roma songs and music and they exposed me to pop American songs (rock and rap) and music. We talked a lot about their favorite music and enjoyed listening to it. One girl even brought a flute because she played in an orchestra to play during our artwork. We also watch a movie about Roma life and art, Latcho Drom.

To approach the task of making the big-sized pictures, I

asked the children to make sketches on individual small sheets of paper. Then we

all examined and judged all sketches to select the best figures that should go

on the big pictures. I told them about a paper collage technique. The children

were surprised to learn that the paper collage was not what they had been

thinking about. They thought that paper collage was only about cutting

ready-made figures of people from journals and putting different parts together.

This technique that I taught led the children to use journals differently:

instead of focusing on pictures on the journals, they had to tear journal pages

apart, to select desired colors, and glue them together in appropriate places of

the picture. When the children understood the technique, they started working

with enthusiasm.

Wilmington

children working on paper collage together

The work on the big pictures forced the children to

actively collaborate. They had to coordinate their work and to participate in

joint decision making with each other about what colors to select, how and where

to place figures, and how to create new shapes using small pieces of papers.

They were very proud of their work. When other children of the Club came to

observe their work, my students proudly announced to them that they were a very

special group because they were making “Slovak Roma art!”

Aaron Liounis (11)

and Vanessa Lewis (12) proudly

show the teamwork Musicians, paper collage,

Boys and Girls Club, Wilmington, DE, USA

The children’s work on the second big picture was motivated by the history of Cinka Panna (Panna Cinková), a famous Roma musician. The children listened to the story with great interest. They wanted to make a picture of her. I had not shown them a picture of her, not even the artistic renditions created by my Jarovnice students of Cinka Panna. I wanted the children to rely on their own imagination. Again, I asked them to make small individual sketches and then select the best parts of them (i.e., they took head from one sketch, hands from another, body from a third) to apply them to the big picture. Again, it forced them to collaborate, to adjust the parts and coordinate their work. This time I offered a new technique for them – finger-painting. To force them to mix colors, I gave them only 5 colors (brown, yellow, orange, white, and black). While they were working, I brought Roma music to inspire them.

Jan Sajko with American

Cinko Panna, teamwork, finger-painting

Wilmington, DE, USA, August 2000

At the end of the project on August 12, 2000,

together with children we went to Washington DC. We visited Slovak embassy and

met with the Slovak consular in Education and Scientific affairs, Dr. Miroslav

Musil. The children presented him with a picture about the friendship between

American children of Wilmington and Roma children of Jarovnice. Dr. Musil

awarded the children with a certificate of Excellence in Roma Art.

Meeting at Slovak

embassy with Dr. Musil,

Washington DC, August 12, 2000

In Washington, we also visited an Art museum. Several days

after the visit, the children and their parents came to the University of

Delaware for an art exhibition of their and the Jarovnice students’ artwork. I

hope that they got memorable experiences out of our work together and meeting

with other cultures.

![]()

Please, leave your comments about Jan Sajko's work and this website in Guestbook

![]()

Recommended films and books about Roma people:

|

|

Romany Trail parts I, II (Jeremy Marre), Editor Roland Amstrong 1982, Harcourt Films |

|

|

Latcho Drom (Tony Gatlif) |

|

|

Katizi the book by Katherine Taikon (in Sweden or Czeck). I found this book most influential on children (and adults) about multicultural problems in general and about Roma (minority) problems in specific. |

![]()

hits since August 23, 2000